You’ve probably never paid much attention to that little percentage next to the protein on nutrition labels. Most of us just look at the grams, right?

Well, that tiny number actually reveals something very important about your protein that almost nobody knows about.

Highlights

- I created a Protein Quality Calculator to help take the guesswork out of figuring out whether or not a product is truly a good source of protein.

- The PDCAAS is a method of scoring protein quality used by the FDA and reflected on food labels as the protein’s %DV.

- Certain proteins are superior to others for muscle building, but all proteins can contribute to your muscle-building goals as long as you are consuming adequate amounts of amino acids.

I recently made a video about protein quality that gained quite a bit of traction, and it seems like I opened a can of worms. A lot of people were completely unaware of how protein labels actually work, so I’m here to help you out.

In this post, I’m diving deep into the world of protein quality, PDCAAS scores, and what it all actually means for your nutrition goals.

Protein Quality 101: Not All Proteins Are Created Equal

We’ve all probably heard about “complete” and “incomplete” protein by now. But what does that actually mean?

Basic science tells us that protein is made up of amino acids. Think of amino acids as building blocks that your body uses for everything from muscle repair to hormone production.

There are 20 different amino acids, but 9 of them are considered “essential” because your body can’t make them on its own. You need to get these from your diet.

A complete protein contains all nine essential amino acids in sufficient amounts. Most animal proteins (meat, eggs, dairy) fall into this category.

An incomplete protein is missing or low in one or more essential amino acids. Many plant proteins fall here, as does collagen (which lacks tryptophan entirely).

But here’s the important part: protein quality isn’t just about having all the amino acids, it’s also about how easily your body can digest and use that protein.

And this is where PDCAAS comes in. It’s an unnecessarily long acronym, but it’s an important one.

PDCAAS: The FDA’s Protein Quality Measurement

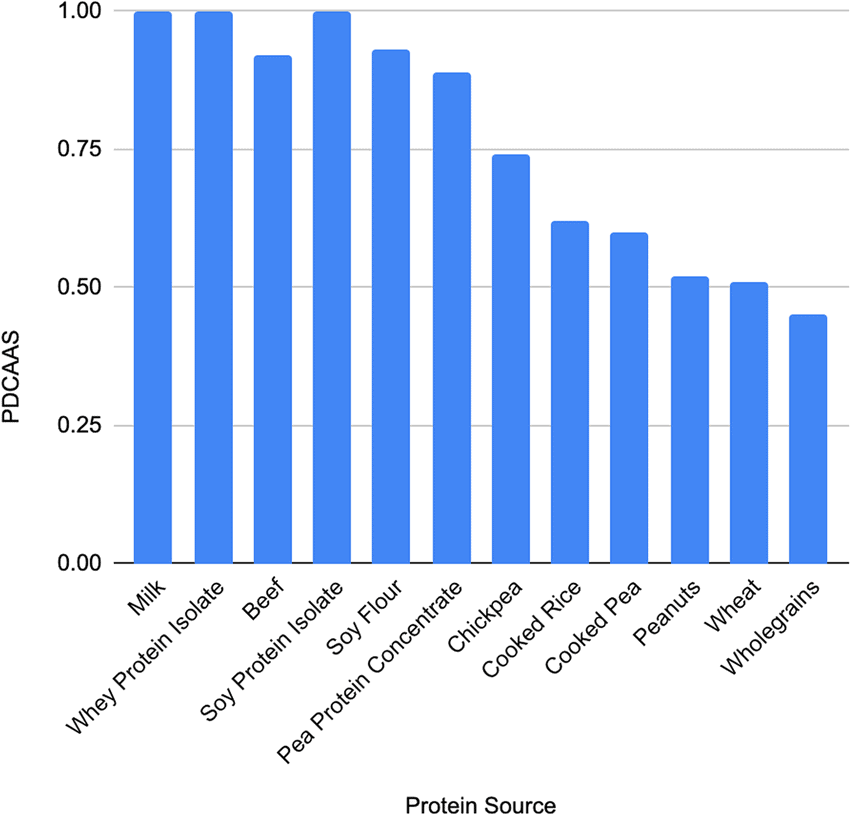

PDCAAS (Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score) is a mouthful, and it’s also the official FDA method for evaluating protein quality. It measures two things:

- The amino acid profile (how complete the protein is)

- How digestible that protein is (how much your body can actually absorb)

The score ranges from 0 to 1.0, with 1.0 being the highest quality. Here’s how some common proteins score:

- Whey, egg, and casein: 1.0

- Soy isolate: 1

- Beef: 0.92

- Pea protein concentrate: 0.89

- Black beans: 0.75

- Rice: 0.5

- Wheat gluten: 0.24

- Collagen: 0.0 (yes, seriously. It’s missing tryptophan entirely)

Now, I know what you might be thinking. No, collagen isn’t completely worthless. And pea protein isn’t necessarily inferior to soy protein.

The score only tells you how effective that protein is in isolation. We’ll talk about that more in a minute.

Protein %DV And Why It Matters

Here’s where things get pretty interesting.

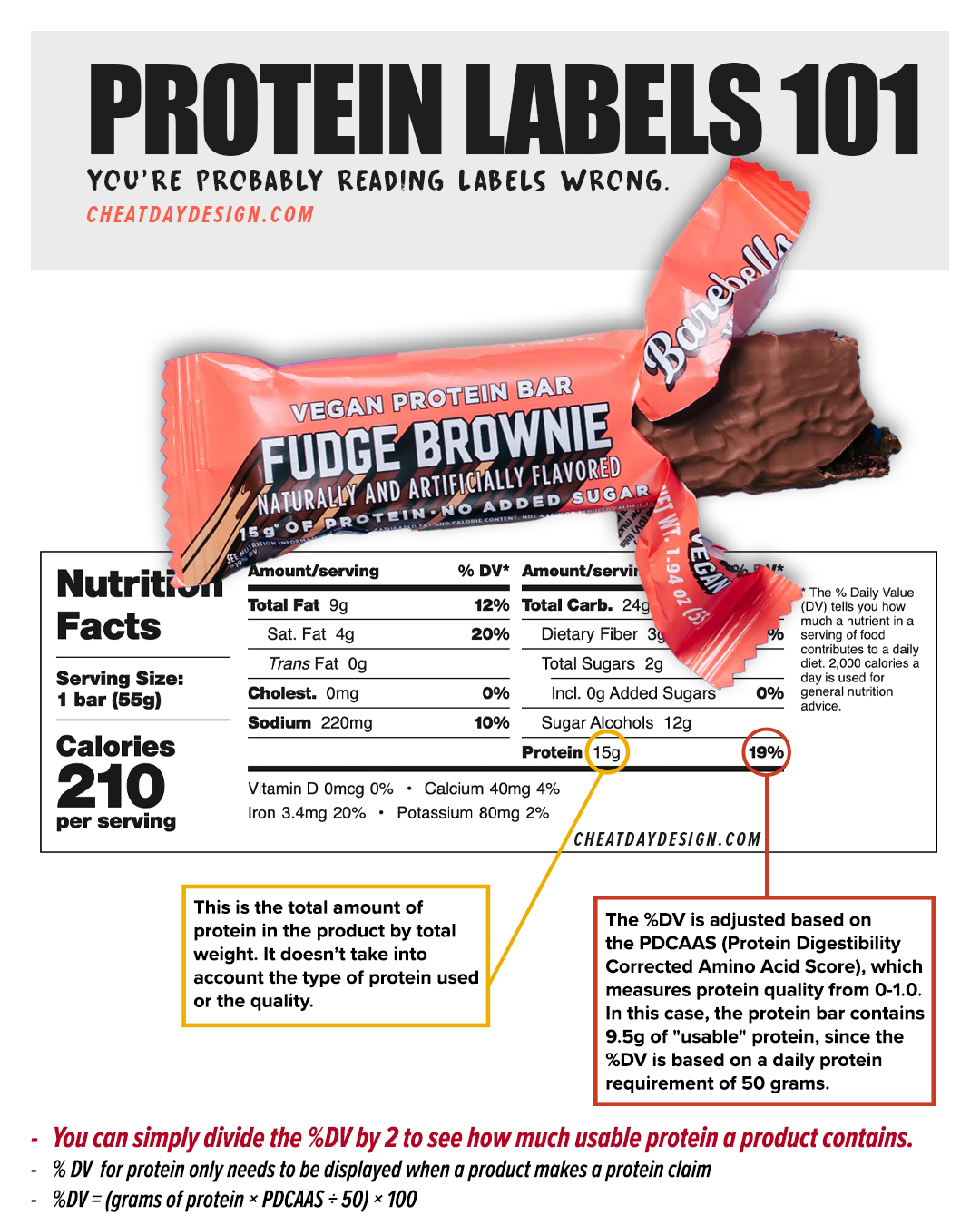

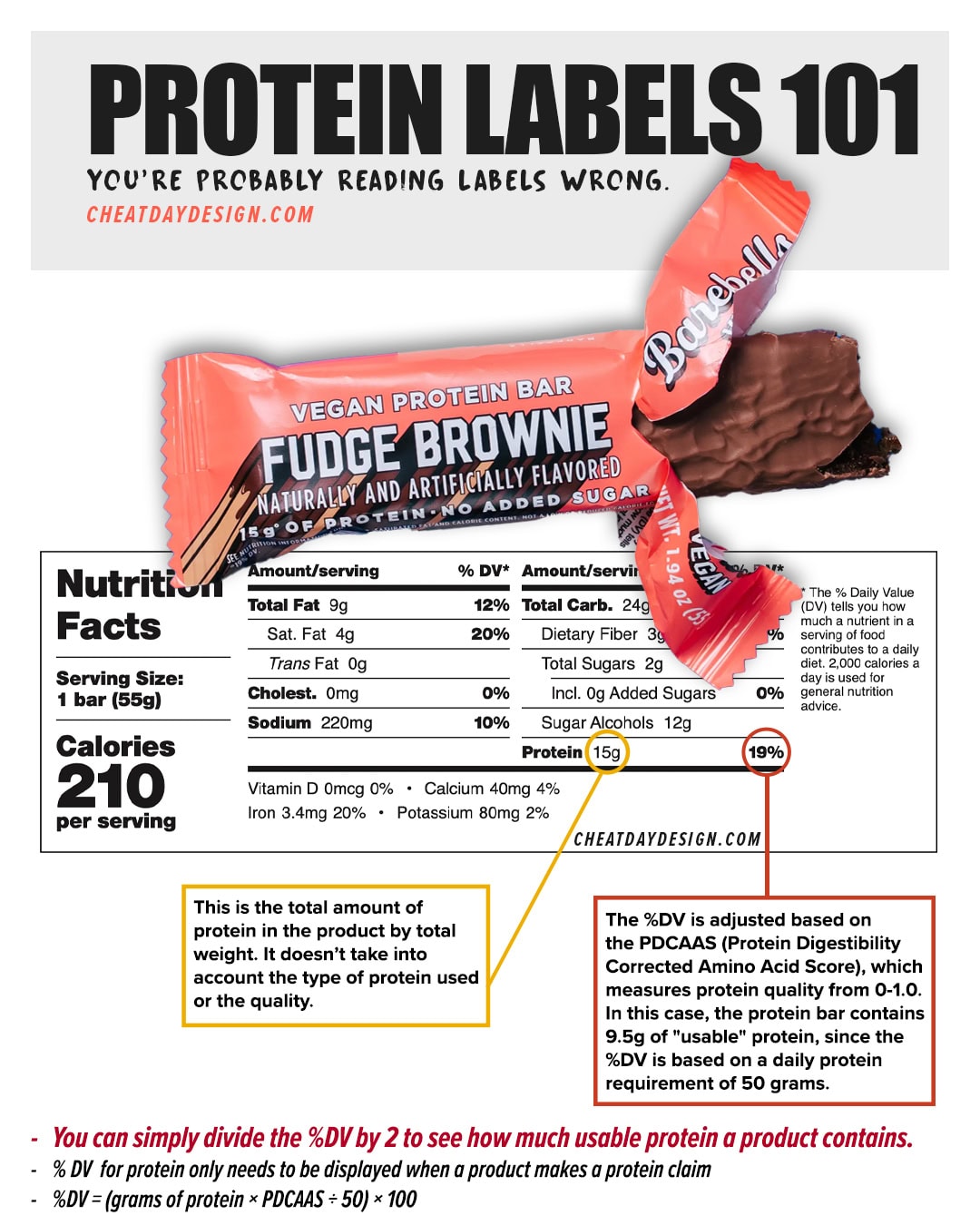

The FDA requires something that most people have no idea about: when a company makes a protein claim on their product (like “high protein” or even just a prominent “20g protein” on the front), they must adjust the % Daily Value based on the protein’s PDCAAS score.

The grams of protein on the label don’t need to change, as that is the total amount of protein is in the product. But the %DV is adjusted to show you the true “usable protein” based on the PDCAAS.

The FDA uses 50 grams of protein as the daily requirement. That is very low (you can calculate your own protein needs here), but that is because it’s based on avoiding malnourishment, not optimizing gains.

The %DV is then calculated as (grams of protein × PDCAAS ÷ 50) × 100

So a protein with a perfect PDCAAS of 1.0 is straightforward:

- 20g of whey protein = 40% DV (20 ÷ 50 × 100)

But a protein with a lower PDCAAS gets adjusted down:

- 20g of wheat protein (PDCAAS 0.4) = 16% DV (20 × 0.4 ÷ 50 × 100)

I know, the numbers get overwhelming. But this all gives us a very simple hack for figuring out how much high-quality protein is in a product:

You can divide the %DV by 2 to see how many grams of “fully usable” protein you’re actually getting.

Let’s look at some real examples:

- A Quest Bar: 20g protein, 40% DV = 20g high-quality protein

- A Lenny & Larry’s Cookie: 16g protein, 10% DV = only about 5g high-quality protein

- Premier Protein cereal: 20g protein, 20% DV = just 10g high-quality protein

When a product doesn’t list the %DV for protein at all (when they should), that’s often a red flag that the protein quality is poor and they do not want to disclose it.

Is Low-PDCAAS Protein Useless? (Spoiler: No)

When I made my video, I used the term “usable protein” as a simplification, and that caused some confusion. So let me be super clear: your body doesn’t just waste protein with a low PDCAAS score.

ALL protein gets digested and absorbed by your body. The amino acids all enter what nutritionists call your “amino acid pool.”

Think of that amino acid pool as a literal pool that your body draws from for various functions.

The difference is efficiency. Proteins with higher PDCAAS scores are more efficient, specifically for muscle protein synthesis, because they provide all the essential amino acids your body needs in one convenient package.

Low-PDCAAS proteins still have nutritional value, they just aren’t as efficient on their own for building muscle. But they still contribute amino acids to your body’s pool.

The truth is, your body doesn’t care if the amino acids came from one “complete” food or multiple “incomplete” foods; it just needs all the essential amino acids in adequate amounts throughout the day.

This is why traditional food combinations exist in virtually every culture:

- Rice and beans (Mexico)

- Hummus and pita (Middle East)

- Tofu and rice (Asia)

These combinations complement each other’s amino acid profiles.

While beans are low in methionine but high in lysine, rice is high in methionine but low in lysine. Together, they form a more complete amino acid profile.

Your body doesn’t need every single protein source to be complete. It just needs a variety of proteins throughout the day (or even better, in the same meal) to get all the amino acids it needs.

What This Means For Different Diets

For Omnivores

If you eat a varied diet with animal proteins, this whole PDCAAS thing is mostly academic. You’re likely getting plenty of high-quality protein and don’t need to stress about it.

The %DV trick is mainly useful for comparing protein supplements and bars when you’re trying to maximize protein efficiency, but you otherwise won’t need to stress about incomplete protein sources.

For Plant-Based/Vegan Eaters

Vegans can absolutely build muscle and meet their protein needs, but they do need to be a bit more strategic:

- Eat a variety of plant proteins to ensure you get all essential amino acids

- Consider a slightly higher total protein intake to compensate

- Pay attention to leucine content, as it’s crucial for muscle protein synthesis (lentils, tofu, and pea protein are good plant sources)

A Note About Collagen

I previously wrote an article stating that collagen should count 100% toward your protein macros. After diving deeper into PDCAAS and protein quality, I feel like I need to give some additional context.

Collagen has some amazing benefits for joints, skin, and hair, and it does provide amino acids your body can use. But with a PDCAAS of zero (due to its complete lack of tryptophan), it’s far from ideal as a primary protein source.

If you’re using collagen as a supplement and eating a variety of other proteins, go ahead and count it toward your total. I prefer to keep things simple, and for the vast majority of people, you don’t need to overthink it.

But if your main focus is building muscle or athletic performance, you shouldn’t rely on collagen as your main protein source. Think of it more as a specific supplement for joint/skin health that happens to contain protein, rather than a primary protein source.

Should it count towards your protein goals? Sure. But it should be 10-20 grams out of the 150 grams you’re aiming for (that’s a completely random number, but you can calculate your own protein needs here), so it won’t move the needle much in either direction.

As long as that “amino acid pool” we talked about is full, the collagen will fare just fine.

Amino Acid Supplements

If your diet is lacking specific amino acids, supplements may be the route you decide to go. And when it comes to amino acids, there are two main supplements: EAAs and BCAAs.

Essential Amino Acids (EAAs)

If you rely heavily on lower-PDCAAS proteins (like plant proteins or collagen), EAA supplements can help fill in the gaps for you.

They provide all nine essential amino acids, ensuring your body has everything it needs for optimal protein synthesis.

This is particularly useful for:

- Vegan athletes trying to maximize performance

- People who use collagen as a significant protein source

- Anyone eating a limited variety of protein sources

Branch Chained Amino Acids (BCAAs)

The other main supplements you will see are BCAA supplements. There are 3 branched-chain amino acids, and they are actually included in EAA supplements already.

Why would you take a BCAA supplement instead of an EAA supplement in that case?

- BCAA contain fewer amino acids, making them more affordable.

- Branched-chain amino acids are specifically geared towards muscle building.

Many companies have moved away from offering BCAA supplements in favor of EAA supplements, which makes a ton of sense. But a case can be made for BCAA supplements if you know your diet is lacking a specific amino acid.

If we look back at the collagen example from earlier, we know that collagen completely lacks tryptophan. Tryptophan is not a BCAA, meaning that if you want to supplement your collagen intake specifically, you’ll need to look towards EAA supplements.

The Bottom Line: What This Actually Means For You

After all this technical talk, here’s what you actually need to know:

- The protein %DV on labels reveals the quality and usability of the protein. Divide by 2 to see how many grams of “complete” protein you’re getting.

- This matters most when:

- Comparing protein supplements or bars (get more bang for your buck)

- You rely heavily on a single protein source

- You’re trying to maximize muscle growth

- For most people eating a varied diet, this is all just “good to know” information, but nothing you need to stress about. You’ll naturally get all the amino acids you need through different foods.

- Protein quality exists on a spectrum: lower PDCAAS proteins aren’t “bad,” they’re just less efficient on their own.

- Companies use this knowledge to their advantage, advertising high protein content while using cheaper, lower-quality proteins. The %DV reveals the truth.

- Collagen has benefits beyond being a protein source. Use it for its unique properties, but don’t rely on it as your primary protein.

Most importantly, don’t overthink this.

Nutrition doesn’t have to be complicated, and obsessing over protein quality won’t make or break your results unless you’re an elite athlete or have very specific goals.

For the vast majority of us, simply eating enough total protein from varied sources is more than enough.

But now that you know how to read between the lines of protein labels, you can make more informed choices about which protein bars, powders, and “high-protein” foods are actually worth your money.

And that’s something worth knowing.